disease is the main contributor to indirect maternal mortality, accounting for almost 33% of deaths of pregnant women.[1–6]. Furthermore, the risk varies depending on the underlying cardiac condition, with maternal heart disease occurring as a complication in approximately 4% to 16% of pregnancies in women who have previously diagnosed cardiac disorders [7–9]. According to estimates, managing cardiovascular diseases could prevent up to 68% of pregnancy-related deaths [1,10]. One of the most difficult clinical situations is cardiovascular arrest during pregnancy. There are significant and distinct differences between resuscitating an adult and a pregnant person, even though they share many traits. The most prominent difference is that there are two patients: the mother and the foetus [11]. First, resuscitation within the "golden hour" commonly goes unperformed due to subpar pre-hospital care, a lack of experienced professionals, and improper inter-hospital transfers. However, the results of polytrauma in pregnant women are frequently fatal [12]. Cardiac arrest during pregnancy is a serious condition that can cause significant morbidity and mortality for both the mother and the unborn child [13]. Cardiac arrest in the third trimester of pregnancy has implications for the neonatal injury and its survival if not immediately intervened [14]. Maternal cardiac arrest is an indication of severe maternal morbidity or unanticipated effects of labour and delivery that have a considerable negative impact on a woman's short- and long-term health. These conditions can result in pregnancy-related deaths if they are not promptly diagnosed and treated [15]. In order to facilitate the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target of less than 30 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births by 2030, it is essential to estimate and focus on this mostly preventable cause of maternal mortality [16].

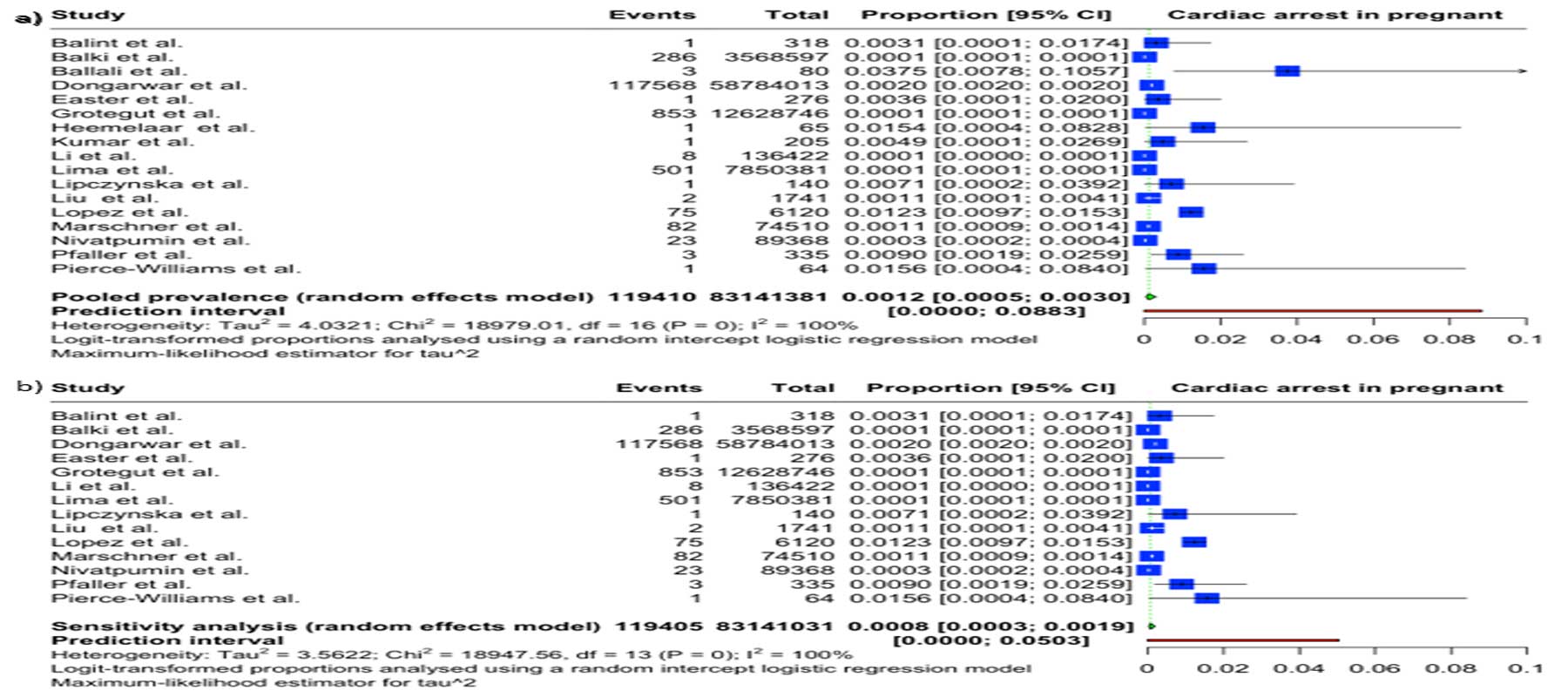

National-level population-based research from the United States of America (USA), Canada, the United Kingdom (UK), and the Netherlands reveals that between 1 in 12,000 and 1 in 36,000 pregnant women experience cardiac arrest [17–20]. In a recent cohort study in the United States, cardiac arrest occurred in one among every 9,000 hospital deliveries from 2017 to 2019, and nearly seven out of ten women survived the incident [21]. The cardiac arrest rate from 2017 to 2019 was 13.4 per 100,000 delivery hospitalisations. Among them, 68.6% of the patients who experienced cardiac arrest made it out of the hospital. In another study from Thailand, 23 women experienced cardiac arrest out of 89,368 deliveries from 2006 to 2015 (1:3885), with three of the arrests taking place prior to delivery (1:29,789), [22,23]. According to this study, pregnancy-related hypertension and cardiovascular conditions were the most frequent causes of cardiac arrests. Pregnancy-related cardiac arrests were more frequent than previously reported [19,24,25]. A number of factors, such as those related to anaesthesia, haemorrhage, cardiovascular illness, embolism, uterine atony, and hypertension/pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, are frequently responsible for maternal cardiac arrest and mortality [24,25]. Furthermore, in a study conducted between 2015 and 2019, no cardiac arrest event was reported in the Philippine General Hospital, with 30,053 women admitted for deliveries, of whom 293 had cardiovascular disease [26]. No cardiac arrests were noted in another cohort study from the Swedish population that included 6630 pregnant women [27].

In India, 60% of the heart diseases identified for the first time during pregnancy were later determined to be rheumatic heart disease in 42% of cases and pulmonary hypertension in 33% of cases, 15% of pregnancies experienced maternal cardiac problems, with heart failure being the most prevalent (66%) of these [28].

Overall, the collective evidence from studies regarding cardiac arrest during pregnancy is limited and contradictory. This emphasises the importance of doing a systematic inquiry to determine the frequency of incidents. The contradiction in the findings of the studies makes it more essential to investigate and quantify the issue of the threat of cardiac arrest during pregnancy. This will enable better resource allocation by policymakers towards the problem of cardiac arrest in pregnancy. However, previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been done on the management of cardiac arrest during pregnancy [24,29,30]. In a systematic search undertaken by the authors in the Cochrane Library and the "International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO)", no systematic reviews were in progress or planned on the frequency of cardiac arrest in pregnant women. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to systematically review and present the pooled prevalence of cardiac arrest among pregnant women globally.

Materials and Methods

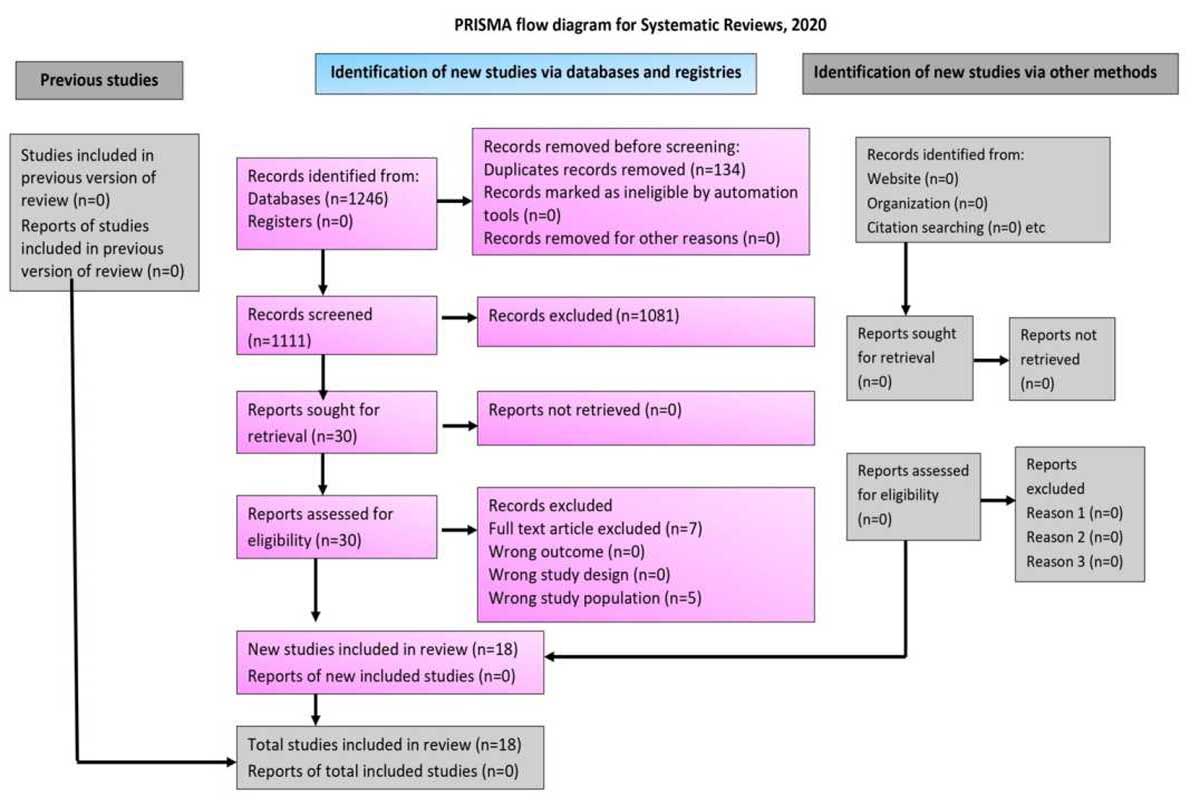

The "Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis" (PRISMA) reporting requirements were followed during the conduct of this study [Table S1]. The study was registered in PROSPERO under registration number CRD42023410718. Informed consent and ethical approval do not apply to the index study because it did not collect data from human participants.

Data source

The research question for the present study was "What is the prevalence of cardiac arrest in pregnant women?", which was elaborated as per the criteria listed in Table S2. Three databases were utilised for the systematic search: Embase, Cochrane, and PubMed [Table S3]. "cardiac arrest," "cardiopulmonary arrest," and "pregnant women" were among the search terms. The search approach and the exact search strings used for each database are listed in Table S3. In order to handle citations, eliminate duplications, and coordinate the review process, we used Mendeley Desktop V1.19.5 software. After removing duplicates, the search results were exported into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

Data Extraction

Two reviewers (SBS and GS) independently assessed the titles and abstracts of studies retrieved from the systematic search.

Figure 1.PRISMA diagram indicating the systematic inclusion of studies for evidence synthesis

Figure 1.PRISMA diagram indicating the systematic inclusion of studies for evidence synthesis

Figure 3. Bubble plot showing meta-regression analysis of effects of a) sample size on proportion of cardiac arrest during pregnancy b) year of study on prevalence of cardiac arrest during pregnancy

Figure 3. Bubble plot showing meta-regression analysis of effects of a) sample size on proportion of cardiac arrest during pregnancy b) year of study on prevalence of cardiac arrest during pregnancy