anesthesiologists and surgeons, consequences and implications, prevention and intervention strategies.

Addiction is stated as a primary chronic illness that involves the brain as the defective organ causing disruptions in neurotransmitter balance [1]. Analogous to other enduring diseases, addiction is characterized by a tendency to recur, lacks a definitive cure, and demands continuous therapeutic interventions [2]. The issue of addictive disease frequently discussed in mainstream media, has often been overlooked by the general public when it comes to physician addiction. It has been indicated that physicians experience addiction at a rate that is equal to that of the broader population [3]. It is evident that physicians tend to reach an advanced stage of addiction before it is recognized and addressed through intervention. This delay in diagnosing physician addiction can be attributed to their inclination to uphold their professional performance and reputation long after their personal life has been lost.

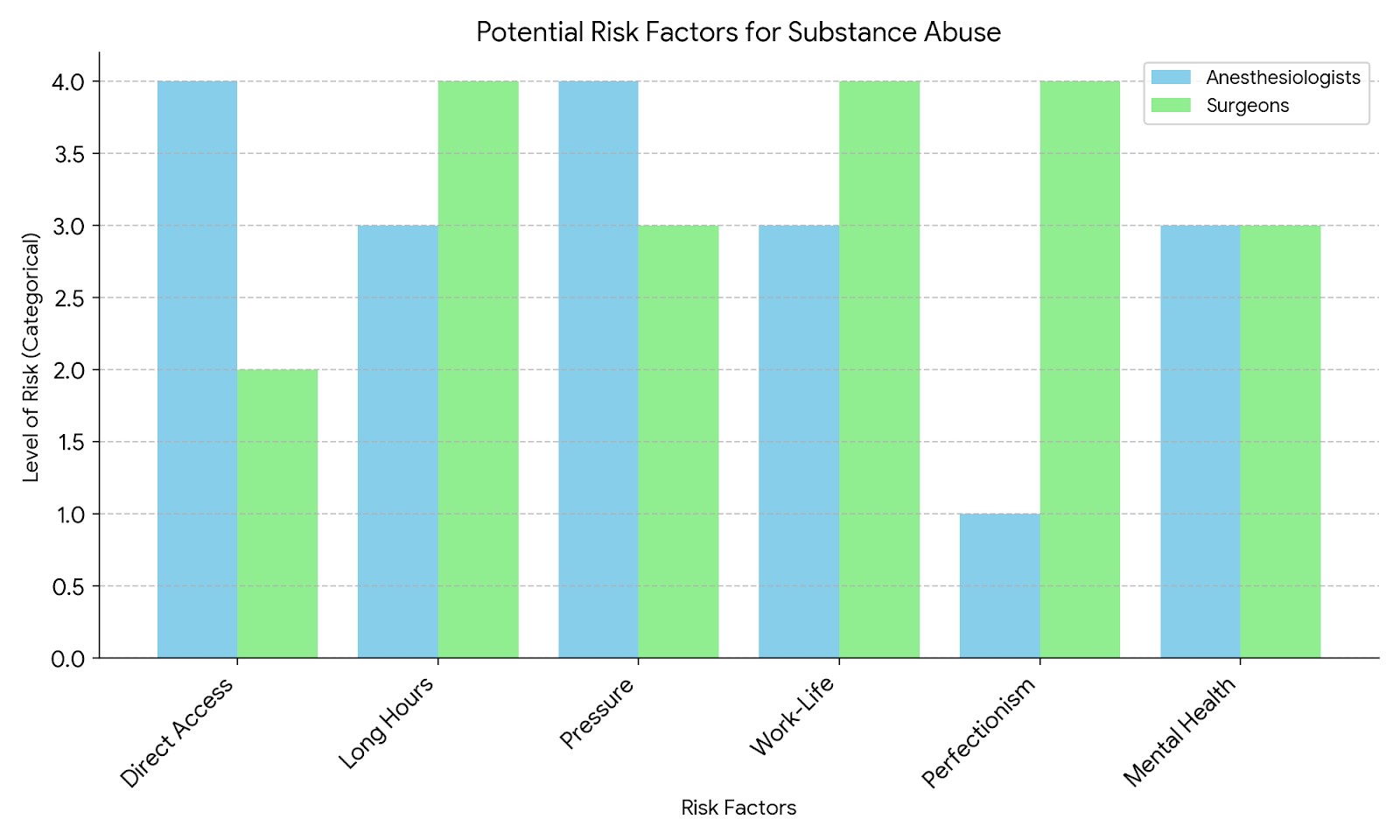

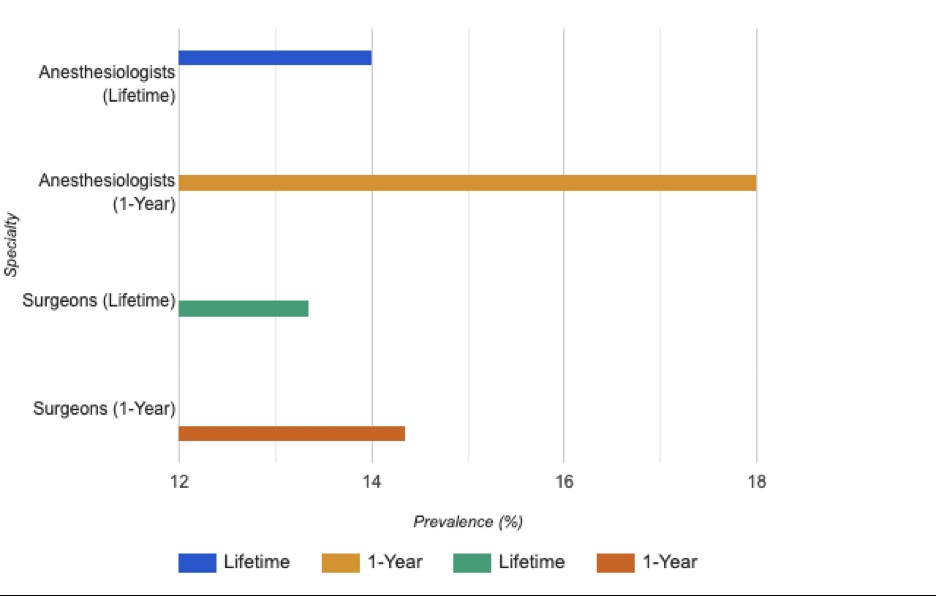

Among the physicians anesthesiologists and surgeons are overrepresented in the case of drug abuse due to certain factors that have been suggested as their proximity to substantial quantities of highly addictive medications [4]. However, the situation for other medical specialists like psychiatrists, who treat severe psychological illnesses, appears to be different. Unlike anesthesiologists and surgeons, psychiatrists typically don't have the same immediate access to large quantities of highly addictive drugs. While they face unique occupational stressors, such as emotional burnout from treating severe mental illnesses, this doesn't necessarily translate to higher rates of substance abuse. Some studies have suggested that psychiatrists might have lower rates of substance abuse compared to certain other specialties, possibly due to their training in mental health awareness and coping strategies [5]. However, it's important to note that physician substance abuse is a complex issue influenced by many factors beyond just access to medications, and data can vary across studies. The relatively straightforward nature of diverting even minimal amounts of these substances for personal consumption, the unmanageable chronic work stress in these specialties, long working hours, bullying, the easy availability of tools like needles and syringes, a higher level of expertise in venous cannulation, and the possession of the highest level of precision in managing the effects of intravenous opioids and other substances prone to abuse all contribute to the problem.

The exposure in the workplace helps to sensitize the reward pathways in the brain, thereby fostering substance misuse. Gold [6] and McAuliffe [7] have recently postulated that anesthesiologists could potentially develop sensitivity to occupationally acquired opioids by inhaling minute amounts of these potent substances present in the air of the operating room. It has been observed that analyses of the air in operating rooms, particularly when samples are collected close to the point of lung-gas exhalation in patients under anesthesia, have revealed the presence of these substances [6-8]. Nonetheless, this hypothesis is based on the assumption that becoming sensitized plays a direct role in the development of addiction and that the concentrations of opioids present in the air are substantial enough to induce such effects.

This issue of physician addiction hampers patient safety and quality of care, as well as contributing to job loss, personal setbacks, and physical as well as mental conditions like vertigo, irritability, anger, and depression. The issue of patient safety has consistently held great significance for anaesthesiologists, with the recognition that anaesthesiology stands at the forefront of addressing patient safety concerns within the medical field [9]. Patient safety necessitates comprehensive patient management throughout the perioperative phase, encompassing pre-anesthetic evaluations, intraoperative care, and postoperative follow-up. Surgeons perform invasive procedures that require a high degree of precision, dexterity, and decision-making skills [10]. Since the addiction alters the state of mind, anesthesiologists and surgeons find it difficult to manage the decision and may not make the right choice. Thus they face severe consequences and legal actions like cancellation of the medical license.

Methods

The methodology for this opinion article involved a comprehensive literature search using databases such as PubMed, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar. Key search terms included variations of “physician addiction," "substance abuse in healthcare," and specialty-specific terms. The review focused on English-language articles published between 2000 and 2024, prioritizing peer-reviewed