malaria vaccine aligns with one of the four key objectives of WHO's Global Malaria Programme strategy for 2024-2030: "Developing and Delivering New Tools and Innovation [1]. This objective prioritizes the evaluation and swift rollout of promising malaria interventions. This focus on new control and prevention strategies propels WHO and its partners towards achieving the ambitious goal of eradicating malaria by 2030. This includes a 90% reduction in malaria deaths and eliminating malaria in not less than 30 countries. And of course, we wouldn’t want the disease to return to countries already free from it, places like Sri Lanka, Cabo Verde, Saudi Arabia and more. That’s the aim of WHO [1]. This article presents the history of R21/Matrix-MTM vaccinedevelopment,its efficacy, findings from clinical trials, and its limitations.

Historical Development of Malaria Vaccines

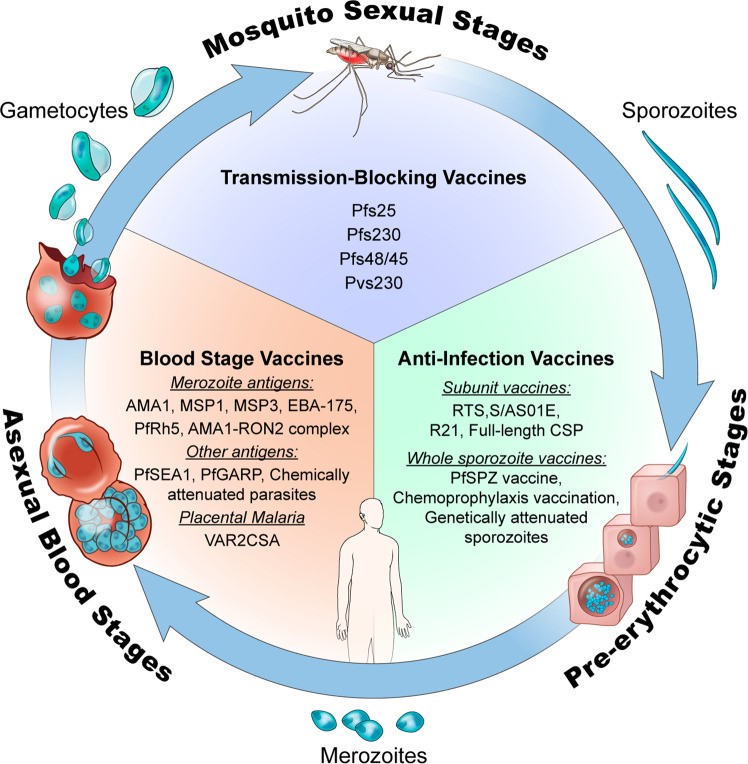

For decades, scientists have relentlessly waged a war against malaria, a top killer disease from a single parasite. This commitment has yielded both setbacks and triumphs. The journey began in the 1960s and 70s with pre-erythrocytic vaccines on the spotlight [6,7]. In the 1970s, Clyde and colleagues launched an investigative human trial of radiation-attenuated sporozoites and observed progressive evidence, even though the trial results did not meet expectations [8].

Figure 1: Life cycle of the malaria parasite and various vaccine types targeting different stages of the life cycle [23].

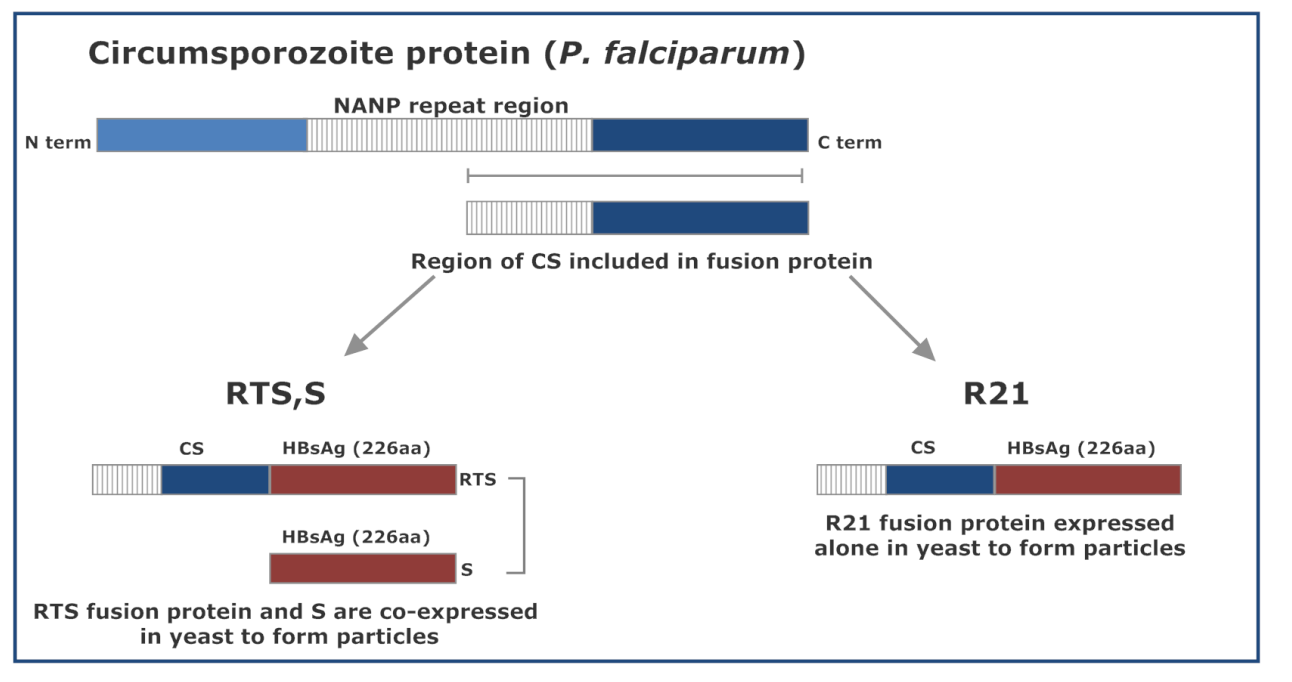

During the 1980s, the first malariaantigenknown as CSPwas identified inPlasmodium falciparum, leading to the development of the subunit vaccine, RTS,S in 1987 [9,10,11]. At that time, a range of vaccines that target the erythrocytic stage of the parasite (merozoites-derived antigens) also emerged [12,13], but trials efficacy was unsatisfactory [9,14,15]. In 2009 through 2019, the