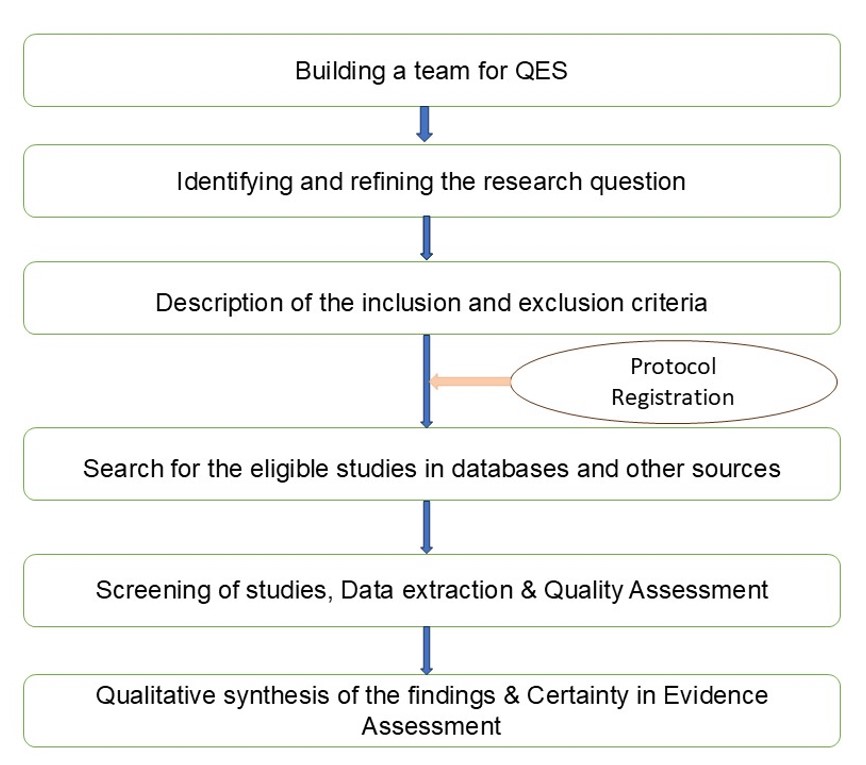

be explored and better understood only through qualitative research. Like quantitative studies, multiple qualitative studies are conducted on same or related research questions across the settings, addressing the qualitative aspects. In this background, synthesising findings from multiple qualitative studies, by pooling their reports is a necessity. Meta-synthesis or qualitative evidence synthesis (QES) is the counterpart of the meta-analysis wherein the studies addressing qualitative research questions are systematically reviewed and synthesised [6–8]. QES is defined as “an approach for synthesising the findings from multiple primary qualitative studies”.[9] It is also defined as “an umbrella term for the methodologies associated with the systematic review of qualitative research evidence, conducted either as a stand-alone review or as a part of a review of complex interventions, systems or of guideline development” [10,11].

Applications of meta-synthesis or QES

Meta-synthesis or QES has found applications in multiple domains. It has surpassed the initial phases where it was used to pool and synthesise only the findings of primary qualitative studies. It has been used in establishing the “relative importance of outcomes, the acceptability, fidelity and reach of interventions, their feasibility in different settings and potential consequences on equity across populations.”[11] In the EBM framework, meta-analysis provides the pooled estimate, which is the high-quality evidence desired for taking out recommendations. Similarly, meta-synthesis can majorly help in understanding the perspectives and preference of the patients and communities (patient values dimension) for whom the interventions are intended [11].

Once the evidence is generated and synthesised, the logical conclusion can take place only after they are transformed into a clinically meaningful guidelines or recommendations. Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks include multiple aspects among which considerations to the stakeholder preference and other specific qualitative factors are involved [12–14]. A context specific, qualitative evidence synthesis on these factors,[11] can complement the quantitative evidence synthesis (meta-analysis) recommendations. Guideline development groups (GDGs) and the policy makers are advocated to consider the inclusion of qualitative findings along with quantitative evidence in the guidelines involving complex interventions. This can assist the key stakeholders to finalise recommendations (decision criteria),[9] which can ensure that the two of the dimensions of the EBM (high quality evidence and patient values) are incorporated in the guidelines. Additionally, QES can enable the mixed-methods review of complex healthcare interventions. This is achieved by following certain integration mechanisms (Segregated design, sequential synthesis) with the quantitative synthesis [13,15] which can again be a crucial informer in guideline development. QES can also aid in the steps of broader policy making process such as defining the problem, identifying programs that could impact the health problem and identifying potential determinants for implementation of the recommendations at various levels and among various stakeholders [16].

Multiple criteria within the EtD framework such as how people value the outcomes, gender, health equity and human rights impacts, acceptability and feasibility have been populated by means of the QES findings [17]. Guidelines on intrapartum-care episiotomy have reported the QES findings assisting to understand the acceptability of the procedure by the women [17–19]. Similarly, QES by Ames et al informed the guidelines on “Communication interventions to inform and educate caregivers on routine childhood vaccination in the African Region – Face-to-face interventions and community-aimed interventions”, specifically in terms of the gender, health equity and human rights aspect [20]. Apart from the decision making on a specific healthcare research question, QES also enables the decision on the scope of the research question itself. World Health Organisation’s (WHO) antenatal and intrapartum care guidelines was informed by the qualitative systematic reviews undertaken to identify the relevant outcomes for the guidelines [9,21,22]. WHO guidelines on digital interventions for health system strengthening, and antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience are examples where QES findings were integral in informing the recommendations [19,23]. Implementation of recommendations has also been guided by the QES findings. In the guideline where epidural analgesia was recommended for pregnant women, [24] QES informed the implementors regarding the setting specific factors affecting the feasibility and acceptability of the epidural analgesia [22].

Thus, QES has a wide range of applications, particularly in fields where understanding complex human experiences, behaviours, and contexts is essential. It informs evidence-based practice by providing a comprehensive understanding of qualitative findings, guiding healthcare practitioners