Addressing SDH through policy actions, that a country needs to take to close the inequity gap in health, is challenging. The Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) provided a model for achieving health equity [2]. Others have emphasized that political, commercial, and environmental determinants also hamper the realization of health equity. However, these determinants are interconnected and have interdependence [3]. The relative importance of these determinants may vary based on the specific health issue, population dynamics, and time frame, underscoring the need for tailored approaches to improve health equity.

The overarching recommendations of the CSDH were to “Improve Daily Living Conditions, Tackle the Inequitable Distribution of Power, Money, and Resources, and Measure and Understand the Problem and Assess the Impact of Action” [2]. At the World Conference on SDH held in Rio de Janeiro in 2011, a global political commitment was made to adopt the SDH Approach to reduce health inequalities [4].

In the last two decades, most societies around the world have been able to improve health outcomes [5]. While improvement in health indicators is a positive step, it doesn't automatically translate to a reduction in health inequities. Context-specific structural interventions focused on addressing health disparities are needed to achieve health equity goals [6].

The literature review of the last decade indicates that few studies on SDH and health inequities have been published [7-9], but academic discourse on social determinants of health and health inequity has been scanty in India. Therefore, we conducted a critical review of the legislations, regulations, policies, and programs in India to find out what efforts have been made and what progress has been achieved in addressing the social determinants of health, especially to find out whether the existing health disparities in gender, caste, economic groups, and regions have improved or worsened at the population level.

Methods

Overall, the study followed a logical framework for the assessment of policy inputs/processes, and outcomes in India using a mix of qualitative and quantitative approaches. With a population of about 1.4 billion, India is governed by a democratic federal political system that includes the Union Government, 28 State Governments, and 8 Union Territory (UT) Administrations. At the local level, there are Panchayats (Councils) in rural areas and Municipal Committees/ Corporations in urban areas. Each of these governing entities has been assigned their responsibilities in the Constitution of India through the Union list, State list, and a Concurrent list of subjects, where both Union and State can act. Local Self-Governments also have responsibilities for specific subject areas as specified in the 73rd and 74th Constitution Amendments [10]. However, this study examined the policies formulated by the government of India after the establishment of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health with special reference to their direct or indirect contributions to social determinants of health equity. The Commission on Social Determinants of Health Conceptual Framework [2] has been used to select relevant policies for this review.

A critical qualitative analysis of the policies in the relevant sectors (Table 1) was carried out to understand the intent and processes in terms of improvements in living conditions, power dynamics, and resource distribution that the government had launched in the past keeping in view the CSDH recommendations. Policies related to SDH were identified from government websites. In addition, PubMed, Web of Science, Science Direct, Google Scholar, and Scopus were used to identify studies in Indian settings from 2012 to 2022. Keywords used in the literature search were ‘Health Equity’ or ‘Social Determinants of Health’, and ‘India’. The contents of the articles and policies were critically analyzed using R Qualitative Data Analysis version 0.3-1, 2018.

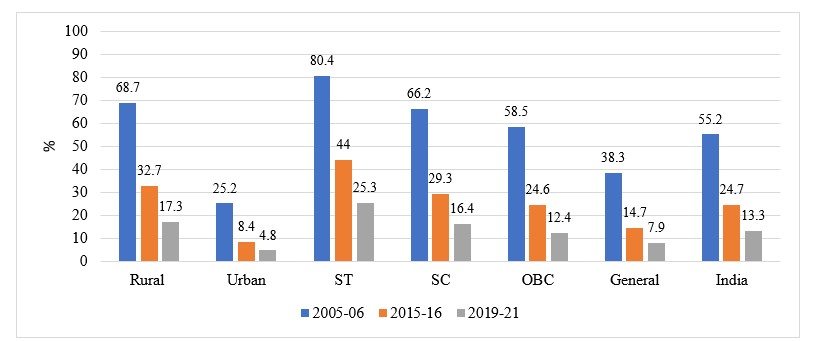

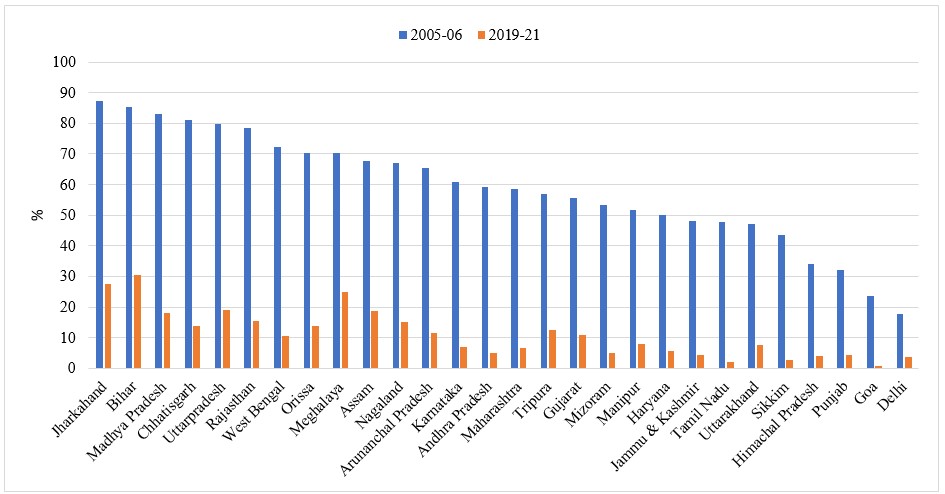

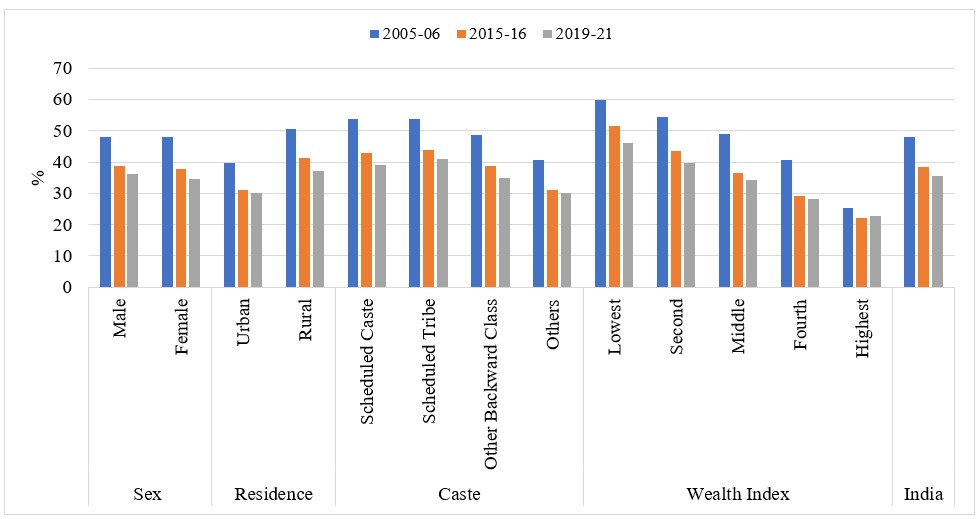

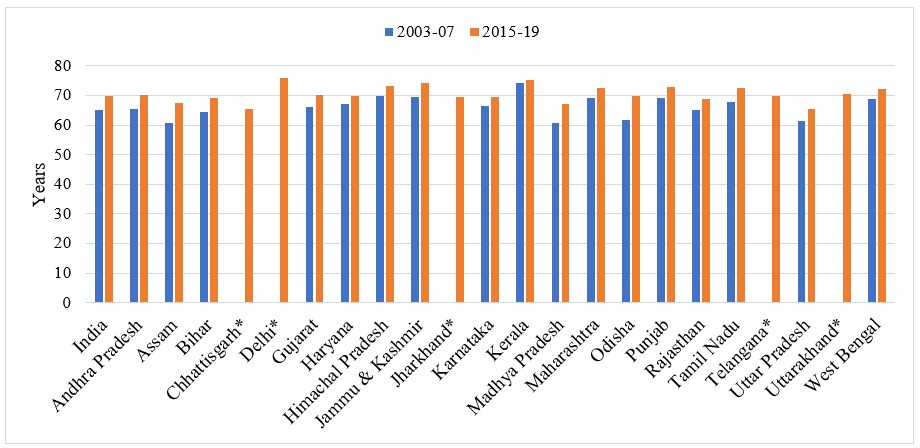

Quantitative data from budget allocations and national surveys were used for assessment of the program inputs and coverage/outcomes. The National Family Health Surveys (NFHS) performed in 2005-06, 2015-16, and 2019-21 provided information on changes in social determinants of health and infant mortality rate [11]. National Sample Surveys have been utilized to explore trends in out-of-pocket expenditure on health [12]. Sample Registration Surveys were used to find out the time trends in life expectancy [13]. Economic Surveys of the Government of India were used to find out financial allocation to various sectors in India [14]. Health equity measures available in these surveys were wealth index, caste, gender, and place of residence. Time trends have been estimated across different population strata in terms of relative or absolute differences.